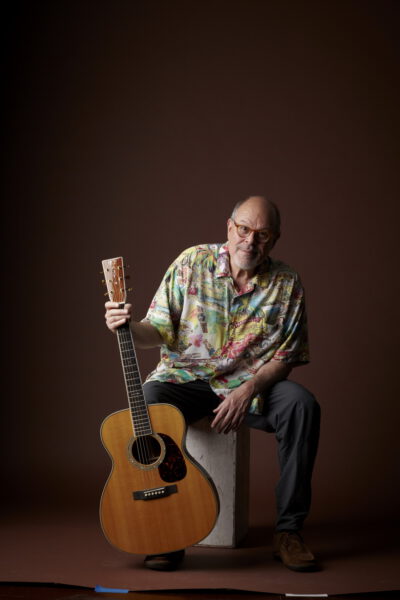

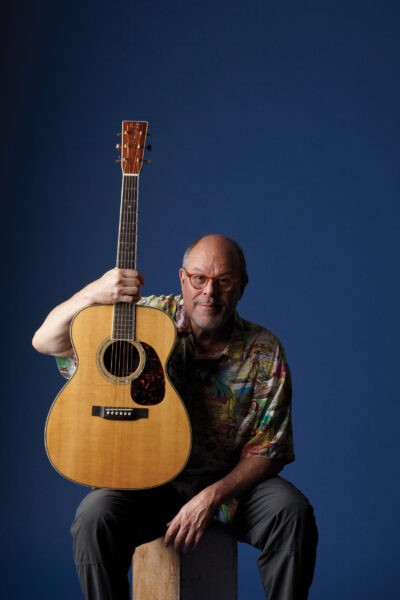

Interview I Stefan Grossman

Interview I Stefan Grossman

Text: Iain Patience

Stefan Grossman is easily one of the most important, significant US bluesmen of his own and a few other generations. Now dividing his time for the most part between the US and Yorkshire, we managed to track him down, even pin him down, for a chat about the music he clearly loves and has been ‘instrumental’ in championing globally.

It would be no understatement to say that this guy is perhaps single-handedly responsible for creating a huge rush of interest in many of the old – sadly, now passed – acoustic blues greats, much of it stemming from his own work with them, his absorbing and mastering their widely varying styles and techniques, and sitting alongside them learning just how it was all done. And, then, where many would have been content with that, he went on to produce some of the finest guitar tablature teaching resource books, albums and videos ever seen, transmitting the skills and music to new generations of neophyte pickers and blues-lovers. Many can testify to his importance in their own personal musical journeys and, as importantly, Grossman always, without exception, provided not just a remarkable baseline to follow, but insisted that everyone must track down and listen to the original artists and their albums whenever possible. Indeed, many blues greats probably owe their own good-fortune in music at the latter stages of their lives to this very imperative.

If there’s an issue when speaking to Grossman, it’s the uncertainty of where to start. This is a man who is an astonishingly talented guitar picker, in a league of his own in so many ways roaring through virtually every type of acoustic finger-picked music from Delta slide styles through Piedmont and general country blues work to the intricacies of ragtime pieces. Add to that the fact he has worked with so many of the greats from Mississippi John Hurt and Reverend Gary Davis to Fred McDowell, Dave Van Ronk, John Fahey and virtually everyone of note in the blues music legacy world.

I start by saying how he destroyed my life in many ways and he laughs uncertainly until I explain having picked up a copy of one of early recordings on vinyl in around 1970, Yazoo Basin Boogie, and being hooked on trying to figure out how he played that style and stuff. At that point, he laughed easily, before going on to explain that he’d been playing guitar a very long time:

‘I really kicked off aged about nine. Between say nine and eleven I was trying to play old standards like ‘Tea for Two’ and ‘Autumn Leaves.’ Really just learning how to read notes and strum a guitar from the American Mel Bay publications. There were these Mel Bay Guitar Books, Methods 1, 2 and 3 and the like. So that’s what I was doing, then I stopped when about twelve because it no longer interested me. Then I was about fifteen I thought it was time that I’d really like to pick up guitar again. My parents were lefties, they said ‘well go down to the Greenwich Village, Washington Square Park and you’ll hear music.’ They had Pete Seeger and Josh White records then. I went into Izzy Young’s shop in the Village and there was a guy working afternoons. He was playing guitar, a song and I liked it. I asked what it was, told him I really liked it. He looked down at me and said it was one of Reverend Gary Davis’s, as if I should know who that was. At Washington Square Park on Sundays from noon until sunset we could get together, play guitar, and a friend told me I should give this guy a call – Reverend Gary Davis. At that time, I had no idea who he was. I called him up and my father asked where he lived. He then told me he had to go there to buy shoes – a lie, because that area of New York was considered the most dangerous of all at that time. So, he drove me up to the Bronx. We were living in Brooklyn at the time.’

‘Not having grandfathers, cos they’d all passed away before I was born, Gary Davis was incredibly important to me personally. David Bromberg and I have discussed it quite a bit, about going into the realm of a really poor black home like Reverend Davis’s. There was just such a warmth there. It sucked you in, besides musically but also emotionally. You just felt wonderful. In a lot of ways, he became a sort of a grandad to me. If I had problems about anything, girlfriends whatever, I’d talk to the Reverend about those and he never once tried to evangelise about Christianity. It was just straight guy-to-guy. Then as far as music, he was phenomenal. You have to think of all the people he taught from Blind Boy Fuller, Larry Johnson, Brownie McGhee and so many white kids, like me. His thing was to always stay two steps ahead of his students.’

‘I never saw myself as being a ‘blues musician’ but rather as a guitar player who was focusing on the black guitar players from the 20s and 30s because they were creating something so distinctive and really new. For me it was like delving into one player at a time, say Lightnin’ Hopkins then Blind Boy Fuller, then Blind Blake. It was their amazing guitar playing. It was like a hobby gone crazy! It was only when I came to England in 1967 and the people I knew, or rather had in my telephone book – I’d met Eric Clapton out in New York where we both did a show together. So, Eric and Ginger (Baker) were the two I knew personally. I came over knowing I could call and stay with them. I’d go out to Les Cousins club and say hello to maybe Bert Jansch or John Renbourn, Martin Carthy. I could gig then with so many folk clubs here. I could actually earn £10 a night! Then if you did two clubs a week, earning £20 a week, you were doing fine.’

I remind Stefan of how Rory Block, his old buddy and then partner had opened the door at their place in Berklee one day to find Fred McDowell there and he immediately recalls it: ‘I remember that. He came and he actually stayed with us for about ten days, maybe two weeks. He was great, another great player in a different way.’

He also recalls how there were a number of different groups, maybe in LA, or Boston, San Francisco, or New York: ‘There was John Fahey, he was Blind Joe Death; I was Kid Future; Rory was Sunshine Kate. We were all still learning how to play the guitar, delving into the intricacies of the art of what had been happening in those 20s and 30s. My friend Tom Hoskins, he went down and discovered, rediscovered, John Hurt. And there was Nick Pearl, he went out and discovered Son House. Everyone got to know each other and we all got to know these great people and players. We all had our own things going on.’

I raise the point about it being an exceptional time with all these guys re-emerging and having a career late in their lives that they must never have truly expected. Grossman chuckles and agrees: ‘One of the things I look back and wonder about, we were all just so niaive, I guess, but we never actually thought about what it must have felt like to them. You know, we’d all sit at their feet, whatever they said were like golden words. And whatever they showed us on the guitar was like amazing! We never thought, oh wait, this must be pretty weird for them. You know, from growing up in Mississippi or wherever and all of a sudden they have all these white kids worshipping them.’

When I mention his exploits with ragtime guitar, he again has instant recall: ‘That goes back again to Washington Square Park. There was a guy, a Rhodes scholar at Oxford, Dave Laibman. He knew Bert (Jansch) and also Alex Campbell. Well, he was playing ragtime not like Blind Blake or Gary Davis, but faithful to the classic rag piano scores. I’m still doing this, the exact same thing I was doing at fifteen years old – now at seventy-five – transcribing Reverend Gary Davis, this week I’m transcribing a bunch of his instrumentals. Davis and his playing really influenced a lot of guitar players.’

Moving to the end, I suggest he has had an impact on so many pickers, maybe because of his own insistence that people listen to original recordings wherever possible, and his production of tablature books, cassettes, CDs and DVDs as learning resources. And with his Stefan Grossman’s Guitar Workshop series, Grossman confirms this still plays a central role in his everyday thinking:

‘When I came over to London in 67, I’d just put together four books for Oak Publications. My idea, and I was very strident about this, was that nobody should learn this music without hearing it. They just must hear it and the way it’s usually taught is by imitation. I wanted the books without music notion but at the end of the day the publisher insisted on that! I wanted the tablature, showing where to put your fingers then to have cassettes alongside these books. Nick Pearl who set up Yazoo Records was supposed to handle the cassettes. That was to be part of his business but he wasn’t interested. I was left with these books coming out and someone had to do these cassettes so I did them myself, as Stefan Grossman.’

In many ways, we’re lucky that Grossman is still out there picking guitar and driving the music forward. A few years ago, he found himself struggling with a serious health issue that had a huge personal impact: ‘I had cervical surgery. It was real troubling, dangerous work on my spine. I’d find myself playing a gig and suddenly my left arm would go dead, absolutely numb and I couldn’t feel a thing. I thought maybe it was time to just stop playing guitar. I’d be in the middle of say Mississippi Blues and suddenly nothing, no feeling at all. I thought about long and hard and had the surgery. Luckily it went well. I’m back picking again.’