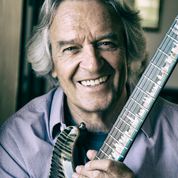

Interview I John McLaughlin

Text: Iain Patience

There are guitarists who are maybe known as being ‘big-hitters’ then there are a few, a handful at most, who might merit the moniker of being ‘huge-hitters.’ UK picker John McLaughlin falls into the latter camp, with a truly astonishing ability and drive that has never slowed, drifted or faltered in what is now over sixty years at the top of the musical tree. Catching up with the guy who is in self-imposed lockdown at home in Monaco, it’s a relief to find him laid-back, interesting and chatty.

McLaughlin has worked with so many of the giants of modern music that it’s hard not to pinch myself as the names slip past like the years, all indicators of his own place in the general scheme, not to suggest theme of things. He confirms he’d hoped to be out on the road touring with 4th Dimension around now, summer 2020, but Covid has laid low his plans, though he hopes the gigs will be rescheduled and possible again next year in 2021. If there’s a difficulty with McLaughlin, it’s probably where to start a conversation!

I elect to go back in time, to his roots and what inspired him personally as a budding guitarist many years ago: “I was about fourteen years old, I think, when I first heard Django Reinhardt. It was amazing, shaped my thinking and gave me some direction in so many ways,” he laughs. When I suggest that may have been a bit surprising at a time when rock and pop were ruling the airwaves, he agrees. “Yea, jazz was not so well known though there were great musicians out there back then. For me personally, Tony Williams was amazing and helpful,” he recalls with a still near-wonderous tone of voice.

Williams was then drummer with jazz giant and pioneer Miles Davis, a band and a musician McLaughlin absolutely loved. “Tony was a revolutionary drummer, the greatest drummer of the twentieth century in my opinion. He was of my own generation and had heard me play on a recording – old style – at a jam at Ronnie Scott’s club in London. He liked what he heard and played it to Miles. I got a call and he asked me to come along to the studio and meet Miles. I was real lucky cause Miles was looking for a guitarist at the time. He was disenchanted with the way jazz was moving. He wanted something else. At the time Herbie (Hancock) was moving away into free-form jazz. I like a sobriety of form and admired what Miles was doing. I went into the studio and played, a baptism of fire, or more accurately a baptism of sweat. I was so tense, I guess. It was a test, I knew, and I passed it and got the job.”

From this start, McLaughlin went on to repeatedly record with Miles Davis, including almost immediately by sitting in on Davis’s ambient jazz release ‘In a Silent Way.’ “Out there in the States, I’d visit his home in Malibu several times a week and we’d play together. I’d played R&B, funk, rock and all those things in the 1960s. With Miles, it was around Autumn 1970, I had a bad night once, playing guitar can be a bitch at times! But Miles knew where I was coming from. He told me it was time I had my own band. So, when Miles Davis says that, you just have to do it!”

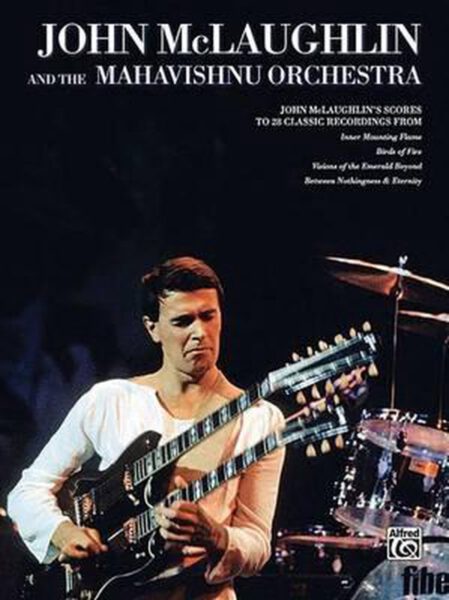

The result was one of the most extraordinary bands of the twentieth century modern music movement, the Mahavishnu Orchestra. McLaughlin remembers it well and was blown away by the immediate success and the way the band were almost instantly embraced by the fans in the USA: “It was all such an unexpected thing. America was so good to us. We couldn’t seem to do anything wrong at the time for the fans. Miles used to come along to gigs and watch us. I’d written a concerto which was recorded by the London Symphony Orchestra. We had a part for flugelhorn and one night after a gig he turned to me and said – ‘Now you can die, John!’ It was an amazing compliment from a guy like Miles. Something I’ll never forget.”

Looking back, he recalls teaching Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page a bit and him being a guy “…with determination and ability. He knew what he wanted.” In addition, he worked in sixties London as a session-man, a life he found unsatisfactory and boring at times, despite working with almost everyone of note at the time from the Stones, Brian Augur, Graham Bond, Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker to a spell with Georgie Fame’s Blueflames. “It was just how it was back then. I had other ideas, I knew I had to get out to the USA.”

Stateside, he then found himself also working and playing with one of the world’s most acclaimed pickers, Jimi Hendrix, with whom he developed a good relationship: “I was working with Georgie Fame and got to know Jimi’s drummer, Mitch Mitchell. Mitch was a huge fan of my buddy, Miles’ drummer, Tony Williams. He’d come along to hang out whenever the chance arose with Tony. He worshipped Tony and his playing. I always say, listen to the Jimi Hendrix Experience and Mitch in particular. There’s a real jazz vibe in there that filtered into Jimi’s playing too. Jimi was living in Greenwich. Village so I got to meet him a lot. One time he was at Electric Ladyland and Mitch said ‘come on, let’s go.’ I went into the studio and I had a hollow body guitar with me. There were a lot of players there and we had a great time playing together, though I still wish I’d had a solid-body guitar with me! But Jimi was just so sweet, so unassuming. It was amazing what he did and could do. Back then he was really pioneering with a guitar, amazing. Listen to ‘Star Spangled Banner.’ Just Jimi, a Strat, a Wha-Wah pedal and a Marshall amp. Astonishing, even now.”

“I feel that Jimi was in ways a bit like John Coltraine. As John developed after ‘Love Supreme,’ he was always looking for more tone and so was Jimi. It was never about noise, always about tone, though Tony Williams always wanted to be loud with his music at the end, John Coltraine’s drummer, Elvin Jones, was another great drummer I knew and admired enormously. He was another great with true vision.”

With enormous global success and acclaim already in the bag, McLaughlin moved on to a new venture with Shakti, a fusion of jazz, funk-blues and Indian Raga-style music that again hit the musical mark. He had a Gibson J200 guitar with a specially scalloped fretboard and an additional seven strings, each individually tuned, that gave him an edge and allowed him to play the Indian rhythmic style and bend notes in a unique way. Sadly, the guitar is no more: “It’s gone now, sadly. An accident wrecked it,” he explains.

Before forming his current band, 4th Dimension, McLaughlin picked up a Grammy for Best Instrumental Jazz Album with his short-lived outfit, the Five Peace Band in 2009. Again, he recalls the pleasure of the award and the album, ‘Five Peace Band Live,’ which he describes as: “Straight-on jazz fusion really. And Chick (Corea) was in a real experimental period at the time. So, it was great to get the award but it was also a surprise in a way!”

When I ask how he found the transition from playing intimate jazz club venues to filling arenas, McLaughlin pauses before responding: “That was unexpected and strange at times. I remember playing with Eric Clapton. – he’s done his bit for guitar too – at his Crossroads Guitar Festival in Illinois. I looked down and there was 110,000 people! Weird to play for such a huge crowd. Eric’s used to that, like Carlos Santana, but it was new for me in reality.”

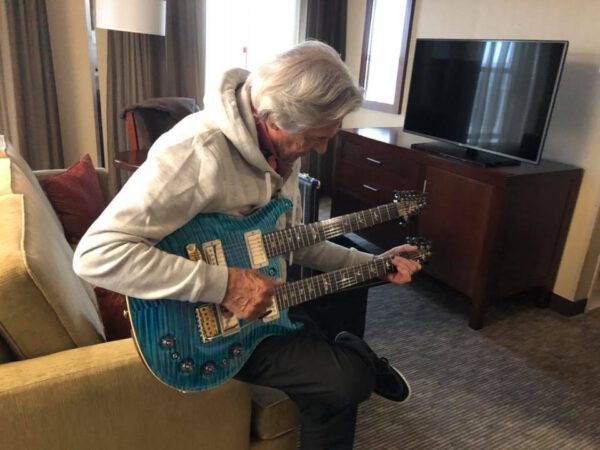

Asked what he’s up to now, he confirms he’s working at home, like most musicians, and is concerned that many musicians will face particularly tough times in the future with Covid and its effects still an unkown. Working on a project to provide some support to his musical colleagues, he has just released a digital download and video performance, ‘Lockdown Blues’ in support of the Jazz Foundation of America, his first recording in around five years.

And with such an endlessly evolving musical history and legacy behind him, it’s maybe worth noting the thoughts of a few other musicians when referring to McLaughlin. Carlos Santana recently told me he considered McLaughlin the greatest guitarist ever. Jeff Beck is quoted as saying: “…..I’d say he was the best guitarist alive.” And his old, late buddy, Miles Davis once said of him: “I heard him play…..and he was a motherfucker!”

As we part company, I wish him well and ask what we might expect in the future: “Well, the tour, hopefully in 2021.Come along and say hello. I’m always working on projects. I can’t imagine life without a guitar to hand. ‘Oobla-dee, Oobla-dah,life goes on,” he sings with a laugh.

Website: John McLaughlin